Unimpeded Movement

Escaping the Mire of Wrath

Choking on Anger

There is one question that has floated through the ether of social media health and mental wellness spaces—so often repeated it might induce an eye roll, almost guaranteed to make you feel silly, and, at the same time, a question even our Cartesian, disembodied world has never fully left behind. “Where do you feel anger in your body?”

While it might be tempting to answer this question with sarcasm (Well, where am I supposed to feel it? In my toes?), I admit, I do have an answer.

I have never been comfortable with my own anger. At some point during graduate school in my early twenties, I took the Myers-Briggs test. It came out INTJ, which, if you’re not familiar, stands for Introverted, Intuitive, Thinking, and Judging—the purportedly rational, logically distanced type. Cool-headed and above the fray. I didn’t really get “angry,” I thought, and I had a whole host of alternate vocabulary to describe what I got instead of angry: irritated, annoyed, or—perhaps most often—frustrated. Often, that frustration would turn inwards, to depression and shame, which seemed to multiply the things I was outwardly “frustrated” about. By the time I was into my thirties, I’d left a toxic church and was well into the brutalizing plod of a PhD program that fed my perfectionist insecurities and left me feeling stressed, undervalued, and—well, stuck.

Technically, I struggled less with Wrath—unmastered, expressed anger—than with its dreary twin, Sullenness—repressed anger. In Inferno, Dante depicts the wrathful duking it out in the marshy, murky River Styx—biting, tearing, and devouring one another in a battle with no victor. The sullen, on the other hand, choke and drown just beneath the surface of the sludge. I like the way Robin Kirkpatrick’s translation renders this passage:

So, stuck there fast in the slime, they hum: “Mournful

we were. Sunlight rejoices the balmy air.

We, though, within ourselves nursed sullen fumes,

and come to misery in this black ooze.”

That is the hymn each gurgles in his gorge,

unable to articulate a single phrase. (Canto 7, lines 121-126)1

If someone had asked me how Anger felt in my body—if I recognized it as Anger at all—it might have been something like feeling frozen, a tightness in my throat, lead in my chest, deadness in my limbs. If it had a color, it would be gray, not red. But more than that, I felt it in my throat, which constricted not just when I was upset but most of the time. I also developed a compulsion to gag whenever I was too stressed. About four years into my PhD, I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disorder (in which, ironically, the body attacks itself) affecting my thyroid (close to the voice).

To be clear, I don’t think anger was my main issue, and definitely not the root. The emotions I struggled with and stuffed down every day were a knotted ball of anxiety, stress, and loneliness, with shame sitting at the center. Anger was the hue that colored the knotted ball, not one of the strings. But that is exactly the point. Anger, expressed or unexpressed, cannot be separated from the more basic emotions that lie beneath it—and when experienced, I believe it can’t be separated from our embodied existence either. “Sunlight rejoices the balmy air,” but wrath and sullenness fester in darkness.

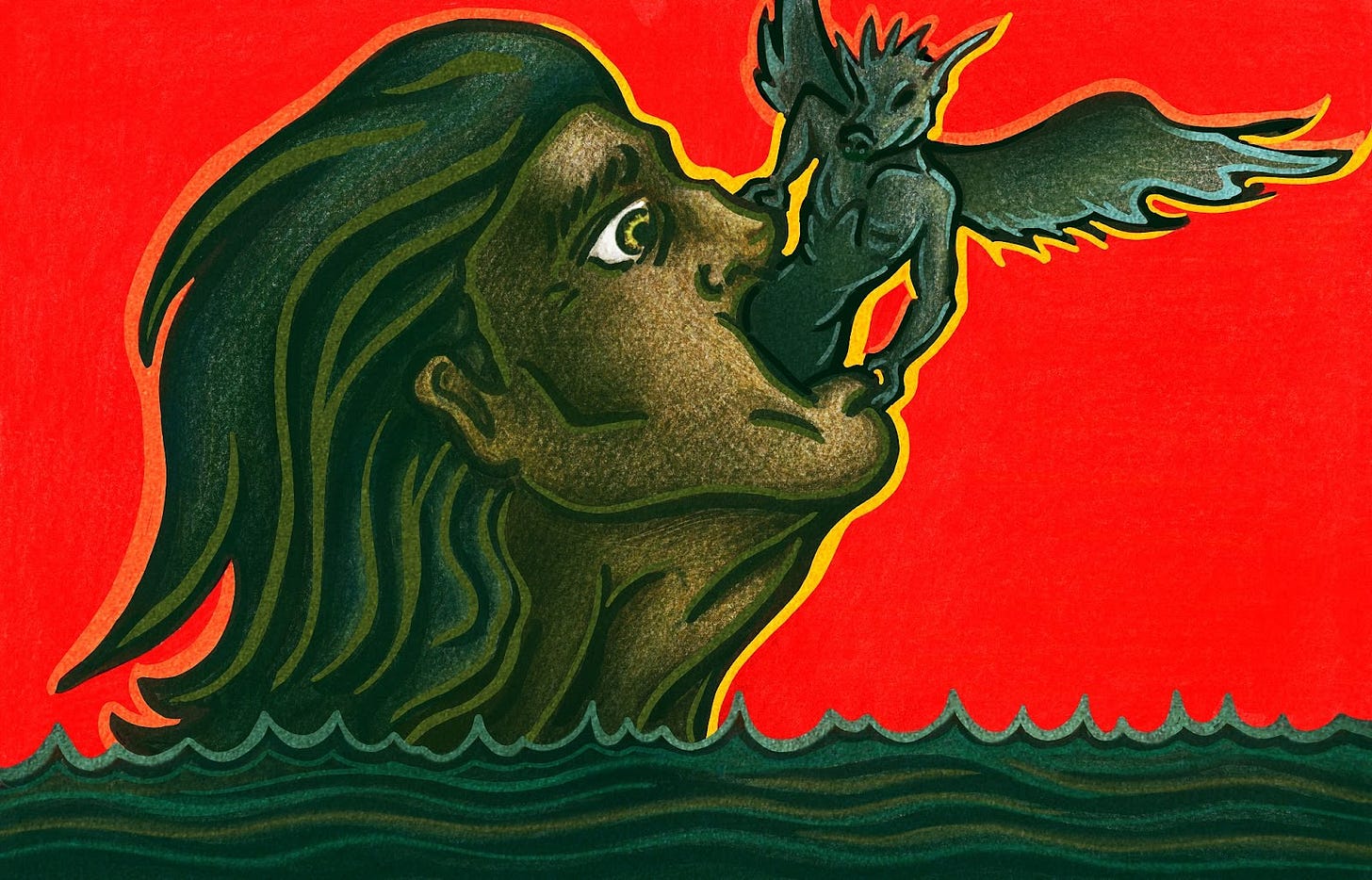

Art by Danielle Pajak, commissioned for this piece. Danielle’s Substack is The Heretical Sayyadina.

Righteous Anger?

I start with the body not only because it is integral to my own story, but because it serves to highlight that humanity is in an ironic situation with respect to Anger. Anger is instinctual, pulling somatic responses along with it—a quickened pulse, flushed skin, clenched jaw, tightness in the throat. Sometimes, Anger is almost indistinguishable from these responses. But while the sins of Pride, Greed, Lust, Envy, Gluttony, or Sloth enlist our emotions along with our wills, we do not speak of them as emotions as such as we do with Anger. Some of us might not even recognize that we carry Anger, that it has become a habit of being. (To mark these distinctions, I will be using “Wrath” to denote inordinate human anger and “Anger” to denote the emotion itself prior to a moral judgment being made.2)

When is Anger just? When is it excessive? When, in short, does Anger become Wrath? Our society can’t seem to decide. The most recent, and direst, evidence of this confusion was the murder of Brian Thompson, CEO of UnitedHealthcare, and ensuing swell of support for the man accused of his murder. That some considered vigilante vengeance to be “justice” was disturbing enough; that Luigi Mangione became an overnight “folk hero” via gleeful and celebratory memes brought to light just how much Wrath is glamorized in our culture. The romanticization of the antihero in popular media is another testament to this.

Christians generally agree that there is a necessary distinction between unrighteous wrath and righteous anger, that at times anger is the proper response to evil in a fallen world. But how easy is it to truly experience righteous anger? In Introduction to the Devout Life, St. Francis de Sales writes, “Depend upon it, it is better to learn how to live without being angry than to imagine one can moderate and control anger lawfully.”3 Hardly what we want to hear. Though Sales’s point might sound harsh, I think it counterbalances a modern rush to exonerate all anger aimed at sin and injustice as necessarily “righteous” in nature.

Thomas Watson, a Puritan, calls God’s mercy His “darling attribute” and God’s wrath His “strange work,” thus identifying it as a response to the disordered nature of evil.4 Of course, fallen as we are, Wrath is far from strange to us. Often, we expect our own anger to be justified by the suitability of its purpose, such that we might be said to be imitating our Lord’s righteous indignation. But what is the nature of that imitation if our own wrath is closer to our hearts than either love or justice?

Let’s dissect this “strangeness” further. Since the time Freud popularized the notion of the Id, we’ve been used to thinking of Anger as a static, morally neutral aspect of ourselves—part of the structure of our very being. Thus, we speak of “channeling” our anger, as if it's a flow that can never be stopped. It’s the unruly child who needs to behave in public. The child can be soothed with treats or worn out by exercise or distracted by amusements. But we don’t dare hope that the child can grow into a mature, loving adult.

Christians, I believe, have absorbed the secular view of the self almost as much as anyone else. Content to manage the outward respectability of our emotions, we often treat Anger as the solid bedrock of our psyches. Traditionally, however, Anger has been regarded in Christianity as a passion that can be directed toward the good (in loving action and confrontation of true evil) or away from it (in Wrath–inordinate Anger, or Anger as an end in itself).

In what follows, I show my debt to the medieval worldview, which characterizes my diagnosis of our current age. The medieval worldview saw all cause and effect relationships—from the composition of man’s soul to the structure of the cosmos—as bound together by a single rational principle: love. Not love as sentiment, but love as the highest, unifying good with God as its ultimate end. In this view, when destructive Wrath takes over, it is we who overturn the harmony of creation. The Roman philosopher, Boethius, showed how disharmony in relationships is just as unnatural as disharmony in the cosmos:

But if love should slack the reins, all that is now joined in mutual love would wage continual war, and strive to tear apart the world which is now sustained in friendly concord by beautiful motion.

Love binds together people joined by a sacred bond; love binds sacred marriages by chaste affections; love makes the laws which join true friends. O how happy the human race would be, if that love which rules the heavens ruled also your souls!5

C.S. Lewis described this same love as “the unimpeded movement of the most perfect impulse towards the most perfect Object.”6 Anger becomes Wrath when it abandons love of God as the ultimate telos and obeys its own ends. It is useless to presume we can imitate God in His anger, without first mastering our passions in accordance with divine love.

Purging Choler

True, Anger is often a response to evil. But as an ultimate state, it will devour you from the inside out. This opens up another question: What does Anger feel like in the political body?

In Richard II, Shakespeare offered a useful analogy for how repressed grievance, divorced from a possibility of justice or healing, sickens the body politic. In one scene, King Richard is breaking up a fight between two men who are outwardly loyal to him. One, Bolingbroke, accuses the other, Mowbray, of embezzlement and political murder, and then Richard steps in:

Wrath-kindled gentlemen, be ruled by me.

Let’s purge this choler without letting blood.

This we prescribe, though no physician.

Deep malice makes too deep incision.

Forget, forgive; conclude and be agreed.

Our doctors say this is no month to bleed. (Richard II, 1.1.156-161)7

What is not directly addressed in this scene is that Bolingbroke’s direct challenge to Mowbray is an indirect challenge to Richard, since Richard is implicated as the author of Mowbray’s crime.8 The ancient practice of bloodletting was believed to enable the overabundant humor—choler, in this case, the fluid of Wrath—to rise to the surface of a wound. Yet, ironically, these lines are spoken by the representative of a body politic that is sick. Richard banishes both men, but this “purge…without letting blood,” in avoiding a cure for the sickness, merely aggravates it. Wrath—as a disordered healing response—is leveraged against Richard himself, who ends the play deposed and executed by Bolingbroke. Uncured choler comes back upon the body of the king, causing grief to the whole political body.9

Cultural critiques of our wrathful society often, and rightly, circle back to the online world. The late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, back in 2016, said that “we are witnessing the birth of a new politics of anger.”10 Even the language we’ve invented to describe the charged atmosphere of digital spaces gives away its ireful character: cyberbullying, trolling, cancel campaigns, and even “rage bait.” We all know that the hyper-connected yet depersonalized world of social media, where avatar interacts with avatar, is bad for us. Yet our society is addicted to provocation. We are overstimulated, yet detached. Full of fiery rage at one moment, yet apathetic and shut down the next. If Anger requires a goal, the internet is designed to guarantee that the only goal fulfilled is the perpetuation of the feedback loop. Relatedly, Jen Pollock Michel’s wonderful post in this series helped us situate Acedia, or Sloth, not simply as “laziness,” but as “failure to engage in effortful good.” This included “the refusal of responsibilities to make true peace” or “to bear a grudge, rather than forgive.” Acedia is the aider and abetter of Wrath, the lying whisperer, telling us that neither good actions nor self-reflection nor prayer are needed. To be righteous–at least, to be better than them–one need only identify with one’s anger. So goes the lie.

There are disturbing consequences. Our culture operates on the judgment that moral evil lies outside the self only, Wrath acting as guardian to keep the “good” actors separate from the “bad.” The fires of Wrath, many assume, are purifying fires. In the twenty-first century, the impetus to direct public wrath towards banishing the guilty, offending, and unclean from the body politic lives side by side with the impetus to eliminate Wrath itself from the individual, body and soul. In fact, I would argue that these are two sides of the same coin. Both are an attempt at “purifying” while ignoring spiritual realities. While the latter is far more rare, it is manifested in the transhumanist’s desire to develop and implement “bioenhancements” to eliminate anger. Susan B. Levin of Smith College writes, “Transhumanists are committed to an extreme form of rational essentialism that includes outright hostility to faculties other than reason, above all, ‘negative’ emotion and mood.”11 While I find this incredibly creepy, it reminds me of my own habit of denying anger because it’s uncomfortable, irrational. In facing my anger, I might have to admit that forgiveness is harder work than shrugging my shoulders, saying “It is what it is” and getting on with life. In forgiving others, I might have to face my own sins and failures and repent. I might have to uncover old wounds. I might have to grieve.

Reasonable as it may seem to eradicate anger as a response, there is nothing truly “rational” about reason divorced from love, and to misunderstand our anger is to misunderstand our loves. This is yet another ironic similarity between the two reactions—the one that banishes the offender and the one that banishes uncomfortable emotion: they both attempt to mechanize virtue by rendering Anger impersonal, something to be weaponized without destroying the wielder, or—as in transhumanism—a glitch in the system, a virus to be deleted. To view Wrath in either mode is to view evil as the gnostics do—a thing in itself rather than as a corruption or perversion of God’s good creation.12

Repudiating Wrath

I hope you have noticed one question that has been implicitly present throughout this piece: How do we reject something that seems woven into the fabric of our being? Dante’s depiction of Wrath in Inferno helps answer this. The fate of the wrathful in the “seething”13 waters is not only mutual destruction but self destruction, as the tearing and biting of the flesh is not merely turned one against another but against the self. Yet, no sooner have the wrathful and sullen been described than, in the next canto, Dante (the character) appears to be fitting right in.

Among the wrathful damned swimming in the sludge is Filippo Argenti, the prideful member of an elite Florentine family, who purportedly slapped Dante during a quarrel and whose family worked against his return to Florence from exile. Argenti approaches the boat, confronting Dante and Virgil. “Weep on,” says Dante, pushing him back into the river to be torn and bitten yet more by his companions. “In grief may you remain, you spirit of damnation!”14

Dante’s apparent hypocrisy threatens to take us out of the story. But Dorothy Sayers has usefully explained the double nature of this scene:

Dante’s pilgrimage through Hell is a pilgrimage made inside Dante. The soul that rises from the mud is only literally the spirit of the Florentine Filippo Argenti; allegorically it is the image of Dante’s sin. In the marsh of Styx, sin for the first time consciously recognises its own ugliness and, for the first time, consciously repudiates itself…Dante, who had honoured the pagans, swooned for pity of Francesca, been sorry for Ciacco the Glutton and felt himself vaguely distressed by the Hoarders and Spendthrifts, turns on Filippo Argenti in horror and invokes the justice of God against him.15

Dante, from the perspective of a modern literalist, seems to be enacting Wrath, but from an allegorical perspective, he’s recognizing his own sin in the sin of his enemy and repudiating it. Leading up to this analysis, Sayers provided context for Wrath’s place as last among the Circles of Incontinence; “...this savage and impotent frustration is the end of the indulgence that began so tenderly” with the sin of Lust, but “which can be traced back even further, to a morality without joy, or, beyond that, to a mere habit of tolerance and indecision.”16 Sins of Incontinence are the soft, delicate sins of self-love and convenience—far removed from the arduous love that “moves the sun and the other stars.”17 Wrath, however, comes rising out of the muck, impossible to ignore. In Wrath, we may, at last, have to face down the ugliness of our own sin and call it what it is.

Herein lies the question for our modern age. Do we recognize ourselves in the images of wrath that surround us? The way to stop devouring one’s self, to escape the mire, is to turn instead on one’s own sins—to hate sin “in here” more than sin “out there.” Wrath, pictured as rejection and repudiation, teaches us what our own response to this sin should be.

Healing Wrath

The structure of allegory in this scene teaches us something else, with finality: you are not your wrath. But while Dante’s allegorical picture shows us what we should repudiate, we should not mistake it for a how-to. Sales advises Christians to calm their wrath by practicing gentleness, not just with others but with ourselves, in order to break the habit:

One important direction in which to exercise gentleness, is with respect to ourselves, never growing irritated with one’s self or one’s imperfections; for although it is but reasonable that we should be displeased and grieved at our own faults, yet ought we to guard against a bitter, angry, or peevish feeling about them. Many people fall into the error of being angry when they have been angry, vexed because they have given way to vexation, thus keeping up a chronic state of irritation, which adds to the evil of what is past, and prepares the way for a fresh fall on the first occasion.18

Healthy anger, I believe, becomes the sin of Wrath not by the greatness of what occasions it, but by our detachment from ourselves, detachment from our communities, and detachment ultimately from God, who helps us name our deeper wounds and bring them into the light. Connection in all of these spheres are the only remedies I know of for the chronic illness known as Wrath.

All these remedies are gathered in what Christ, our Great Physician, provides by means of his own Body—the Body of Christ gathered together in unity and the elements of the Lord’s Table. Visible reminders of ultimate restoration and healing for all wounds.

After attending an Anglican church for a few years now, I’ve grown accustomed to the passing of the peace being pointed to as an act that precedes the Eucharist and as a eucharistic act. You are at peace with God. Be at peace with one another. The first time I visited this church, I hadn’t realized how badly I needed someone to hand me—actually place in my hand—the bread. This is the body of Christ, broken for you. I cried tears that Sunday that I’d stored up for years. The knot inside didn’t unwind all at once, but it loosened.

Though we fall away from the “love that binds all,” Christ opens the way back into full participation in this love, allowing us to say, along with Boethius, “O how happy the human race would be, if that love which rules the heavens ruled also your souls!”

Jennifer Downer is a writer and a humanities teacher at a classical Christian school. She has a PhD in English Literature with a specialization in the Seventeenth Century. If you are interested in topics related to sacramental imagination, the Inklings, literary analysis, or re-enchantment, consider subscribing to her Substack, The Red Sign Door.

If you found something to enjoy or something to challenge you in this article, consider buying her a coffee!

Dante Alligheri, The Divine Comedy, Trans. Robin Kirkpatrick (New York: Penguin Classics, 2013), 33. All quotations will refer to this translation.

These designations are used for the sake of clarity, fully acknowledging that a hard distinction between the words is somewhat arbitrary. For example, when theologians speak of God’s wrath, they are obviously not attributing sin.

Francis Sales, Introduction to the Devout Life (New York: Vintage Books, 2002), 110.

Thomas Watson, Body of Practical Divinity: The Works of Thomas Watson (Monergism Books, 2021), 258, https://www.monergism.com/works-thomas-watson-ebook.

Watson writes: “Mercy is his darling attribute, which he most delights in. ‘Who is a God like you, who pardons sin and forgives the transgression of the remnant of his inheritance? You do not stay angry forever but delight to show mercy.’ Micah 7:18. Mercy pleases him. ‘It is delightful to the mother,’ says Chrysostom, ‘to have her breasts drawn; so it is to God to have the breasts of his mercy drawn.’ ‘Fury is not in me,’ that is, I do not delight in it. Acts of severity are rather forced from God; he does not afflict willingly. ‘For he does not willingly bring affliction or grief to the children of men.’ Lamentations 3:33.”

Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, Trans. Richard Green (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1962), 41.

C.S. Lewis, Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 60.

William Shakespeare, Richard II, Ed. Charles R. Forker (London: Arden Shakespeare, 2002), 187.

A footnote to this passage in the Arden Shakespeare edition notes that “Bolingbroke strategically ignores Richard’s supposed complicity” and that “it was generally believed that Richard ordered his uncle’s murder–or private execution.” Ibid, 187.

The medieval view of kingship was premised on the theory of the “King’s two bodies”--a natural body and a political body, signifying the unbroken rule of kingship in a universal, perpetual sense. See Ernst H. Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

Jonathan Sacks, “Beyond the Politics of Anger,” Jonathan Sacks: The Rabbi Legacy Society, The Rabbi Sacks Legacy Trust, 11 Nov. 2016, https://rabbisacks.org/archive/beyond-the-politics-of-anger/

Susan B. Levin, "Anger and Our Humanity: Transhumanists Stoke the Flames of an Ancient Conflict,” Smith ScholarWorks (2021). https://scholarworks.smith.edu/phi_facpubs/56

In considering how often we view evil as external to us, in doing so, sidestep the hard work of mastering our passions, I’m reminded of a John Milton quote: “Banish all objects of lust, shut up all youth into the severest discipline that can be exercised in any hermitage, ye cannot make them chaste that came not hither so.” “Areopagitica,” Complete Poems and Major Prose, Ed. Merritt Y. Hughes (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2003), 733.

Dante, Inferno, Canto 7, line 101.

Ibid, Canto 8, lines 37-38.

Dorothy Sayers, “City of Dis,” Introductory Papers on Dante (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1954), 138-139.

Ibid, 137.

Echoing and complementing the passage quoted from Boethius, this is the famous final line of Dante’s Paradiso. See Canto 33, line 145.

Sales, 111.

Jennifer, thank you for making me take a long look into my own self with this honest, searching, self-revealing piece. It shows how easy it is to excuse ourselves and to overlook our own sin as nothing, but that we must face it and take it to Jesus for cleansing and healing.

“Do we recognize ourselves in the images of wrath that surround us? The way to stop devouring one’s self, to escape the mire, is to turn instead on one’s own sins—to hate sin “in here” more than sin “out there.””

An excellent and challenging piece full of wisdom. The world is more openly unhinged than ever, anger is like a machine, and herein lies some poignant questions we should ask ourselves before becoming a slave to it.

Bravo @Jennifer Downer! And bravo @Danielle Pajak for the powerful art to accompany it.